Initial release date: July 22, 2004

Platforms: Nintendo Switch, GameCube

Mode: Single-player video game

Composer: Yuka Tsujiyoko

Genres: Adventure game, Japanese role-playing game

Designer: Shigeru Miyamoto

Developer: Intelligent Systems

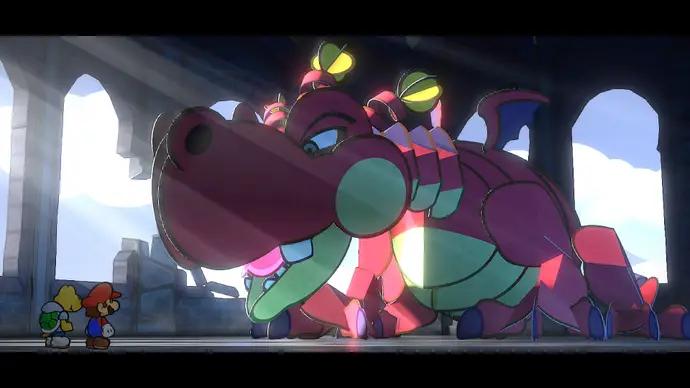

The fact that the same team behind Paper Mario: Sticker Star also developed Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door is so unbelievable to me. For the longest time, Sticker Star and Super Paper Mario served as my only points of reference for the Paper Mario series. I never bothered to play Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door, no matter how many times it was suggested to me—especially considering how much I loved the Mario & Luigi series and, of course, the Super Mario RPG. Thus, it was unexpected to play a game that was so excellent and to experience something that was so lovely in terms of both graphics and music.

Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door has a certain finishing touch. The side missions aren’t much more than fetch quests or riddles, and it’s not any bigger or more open than previous RPGs, but everything feels really purposeful. The instant Mario sets foot in Rogueport, the Paper Mario universe envelops you. Despite being Mario’s sworn enemies, Bob-ombs, Koopa Troopas, and Goombas are all over the streets, adding color to the world. It begs the question, “Why don’t they still make big Paper Mario RPGs of this caliber?” because of all these recognized faces.

Mario learns that Princess Peach discovered this bizarre map, which depicts a door and a large treasure located beyond it. She is urging Mario to visit Rogueport in order to assist her in finding the key that would unlock the door. Peach is kidnapped by someone other than Bowser as Mario takes sail. She fortunately sent Mario the map. Once in Rogueport, Mario meets up with Goombella, one of my favorite characters in the game, and the two of them work together to discover the door, locate the seven stars, and save Princess Peach. Though it’s not quite as good as Planescape: Torment, the setup is nonetheless excellent for a Mario game, and the seven stars are essentially the companions we meet along the journey.

Throughout the game, Mario befriends people who accompany him on his mission and speak for him even though he is mute. Goombella held a significant role in Mario’s strategy since she had the ability to expose an enemy’s HP and stats, as well as provide Mario with little details that help him determine the best way to defeat them. This was a brilliant touch, as it completes the tattle log and keeps you from making mistakes like jumping on a Piranha Plant or taking too long to kill a Dry Bones, even if it effectively wastes her turn. Beyond that, when you meet a partner, their skills are fairly specialized for fighting around. Nonetheless, they are all unique individuals with practical skills outside of combat.

For instance, you can kick goods to activate them or kick faraway objects to collect them with Koops, the accompanying Koopa Troopa. To uncover hidden chambers and objects, one partner can blow incredibly forcefully. You get the idea. The game Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door does a great job of interspersing these bonus regions. As always, Nintendo does a fantastic job with level design, and The Thousand-Year Door is no exception. It takes a fair amount of walking through Rogueport’s sewer system to reach the previously stated Thousand-Year Door for the first time. But after Mario gains a few improvements, the journey moves along lot more quickly as you smash through barriers, uncover useful items, etc.

Battle actions are used in turn-based battles. For those who are not familiar, battle actions take place following your attack type selection. Mario has two ways to attack: using his hammer or jumping on the adversaries, which is perhaps how we’re most used to seeing him do it. Naturally, the hammer is a holdover from his Donkey Kong days. When Mario decides to leap on an opponent, a button called A will appear on the screen, telling you to push it to make another jump once Mario hits the creature. With hammers, you usually pull to the left with your joystick and let go when a star illuminates; it’s similar to quick-time events but not quite as unpleasant. Mario and his allies make use of these battle cues.

The way Intelligent Systems has crafted a Mario world that feels both very lived in and extremely Mario is simply amazing. You visit Rogueport-related locations in each chapter, and they’re all quite Mario-esque. With its arena and emphasis on cult of personality, Glitzville feels like it belongs in Super Mario RPG, whereas Petal Meadows looks like it would be World 1-1 in a contemporary Mario game. In Chapter 5, which takes place on a train, TTYD even plays with the expectations of the player’s experience by placing you in the role of a mystery solver. All of this adds up to a seamless experience that maintains tension both during and after fight while being comfortable with worldbuilding and tempo.

The Glitz Pit in Glitzville, where the story takes place as Mario advances through the ranks in the arena, is where I have the most problems with the pacing. When I play a JRPG, the arena is always the highlight of the experience for me. The 20-battle arena rise by TTYD seems excessive. This felt like a complete standstill, putting me on an unneeded crawl, in contrast to prior chapters when I felt like things were moving along the entire time. Even though I think this is a major flaw in the game, it was just a little setback for Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door.

Writing a review for a game this old feels strange, especially with the praise it garnered. Normally, when I evaluate a game, I explain topics that are known or unfamiliar and sprinkle in my thoughts about the overall design of the game. Much of that information is already known to us from Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door, and not much has changed. Even though there are a number of minor gameplay adjustments, most of them aren’t really significant. Every time you deliver a star to the Thousand-Year Door, you can enter the warp room beneath Rogueport, where a fresh pipe will appear. Hitting the save block no longer prompts you to select which save slot to use, thus you’re stuck with the one you selected when you first started the game. Fortunately, the Mario Wiki seems to have done an excellent job of listing the modifications, albeit most of them would be practically undetectable if played at launch.

All of that adds up to the best way to play Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door, though it may or may not be remarkable depending on your taste in web gaming. Everyone appears to have a different idea about how these remasters should be presented, and, to be honest, this seems about correct. The game looks amazing, especially when viewed on a big screen. Considering that the majority of Nintendo Switch games don’t, it functions remarkably effectively. Updates are made without diluting the experience. This seems to be as near to the original experience as you can get if you’re interested in keeping everything intact.

This is the kind of remaster you want for your game, not just the kind of sequel you want for a series. I wonder if Nintendo is preparing for an RPG renaissance by releasing these incredibly beautiful and authentic remasters. I wouldn’t hold my breath, given the mediocre reviews for Paper Jam and The Origami King.

Review Overview

Gameplay – 88%

Story – 90%

Aesthetics – 85%

Content – 87%

Accessibility – 80%

Value – 90%

Overall Rating – 88%

Excellent

Summary: Nevertheless, the remastered version of Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door is a superb game that pays homage to a highly regarded game in a well-liked franchise. For an RPG enthusiast, sleeping on this entry would be a grave mistake.