Platforms: Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 5, Microsoft Windows, Xbox Series X and Series S

Initial release date: February 1, 2024

Developers: Surgent Studios, Abubakar Salim

Genres: Metroidvania, Fighting game, Shooter game, Adventure

Mode: Single-player video game

License: proprietary license

Composer: Nainita Desai

Few things in life are more painful than losing a loved one. It’s a difficult subject, so I applaud Tales of Kenzera: Zau for focusing entirely on it. Video games are unusual in that they may transmit empathy and emotion by putting you directly in the shoes of the character you control. Given the subject matter, I expected Tales of Kenzera to be a difficult but eventually satisfying experience of parting with someone close to you. Instead, I found my experience with it to be really painless. While I believe this game’s heart is in the right place, I couldn’t help but question if it smoothed off the edges too much. Perhaps parting should not be so easy, lest it fail to have a lasting impact.

I emphasize the story because the game takes a similar approach. The game begins with the kind of cutscenes and forced slow walking parts that you’d often find in big budget, narrative-driven “AAA” games these days. Tales of Kenzera: ZAU is mostly on the escapades of a shaman named, well, Zau. Okay, fair enough. Although his father died recently, Zau intends to bring him back by obtaining a favor from the god of death. This quest takes him around a vast map, fighting monsters, gathering upgrades, and solving obstacles. After these initial sections are completed, it admits to releasing you from its heavy-handed narrative clutches and allowing the actual game to breathe. However, the overarching concept of “narrative first” persists throughout the design.

The beginning portion transitions into what “we” in the “biz” refer to as a “Metroidvania”. Tales of Kenzera, according to the developers and marketing, is a “Metroidvania” game. The term “Metroidvania” is widely criticized as a catch-all descriptor because it suggests that any game with the moniker possesses characteristics common to both Metroid and a subset of Castlevania games. In reality, the vast majority of supposed “Metroidvanias” really just have roots in the “Metroid” portion of the equation, thus you can call these games whatever you want as long as you mention Metroid, from “Metroiders” to “Metroid-em-ups.” I’m thinking “Metroidios” this week. This entire diatribe may come across as semantics, but semantics are important here because, as I played Tales of Kenzera, even the Metroid connection felt shaky in light of the game’s underlying goals.

Tales of Kenzera acquires the moniker “Metroidio” from technicalities rather than a genuine embrace of Metroid’s design sensibilities. Exploration defines Metroid games; they are all about exploring maze-like areas to find your way forward. of contrast, the map of Tales of Kenzera shows the game’s true character. First, the game directs you to the right side of it. After that, it sends you backwards to the left. Then it turns you around for a few screens before sending you all the way to the top.

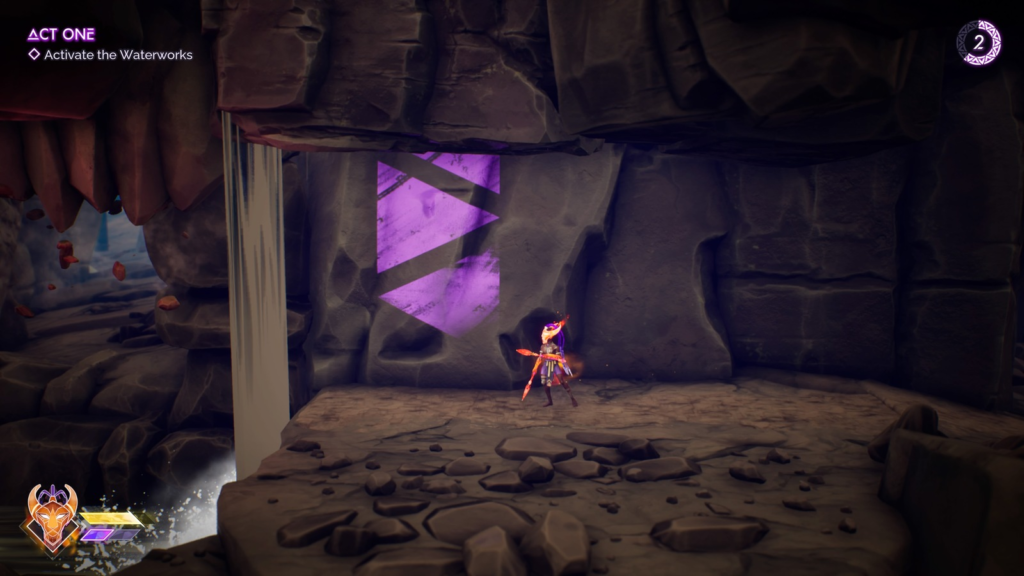

Essentially, the game is made up of a series of straight lines that overlap in small ways. Yes, there are some side pathways with modest enhancements, but they don’t branch far and won’t take up much of your playing. That’s just the beginning of how uninterested Tales of Kenzera is in forcing you to explore. Purple paint scattered around the landscape will indicate paths forward, including seemingly hidden ones. The map does not relate in any meaningful sense. As the story unfolds, it clearly indicates where you’re expected to travel on the map to eliminate the potential of getting lost.

Despite the presence of numerous Metroid characteristics like as a large area and upgrades to obtain, Tales of Kenzera is ultimately more of a straightforward action game with a focus on platforming and combat. The general game structure alternates between these two components. The majority of your time will be spent navigating environmental obstacles with well-timed jumps or using powers like ice blasts to freeze waterfalls and clear a way forward. On your journey onward, you may find yourself unexpectedly confined into a chamber with adversaries and forced to fight them off before continuing.

To Tales of Kenzera’s credit, it’s all quite enjoyable to perform. Zau moves rapidly and precisely, making him well-equipped to deal with the onslaught of platforming ahead of him. Zau can switch between combat tactics on the fly because to the ability to wear masks. The Sun Mask allows him to perform close-range melee attacks, whilst the Moon Mask grants him access to ranged energy blasts. Each mask is ideally suited to a unique situation: the Moon Mask is most effective against adversaries who fly just out of reach, whilst the Sun Mask may incapacitate ground-based enemies with juggle combos.

Tales of Kenzera’s excellent foundation of fundamental mechanics, along with the simplicity of the map design, creates a sense of flow that propels you ahead consistently. While playing, I rarely felt like I was at a dead end or needed to take a break from the game. The next progress milestone was always just around the corner, providing motivation to keep playing for “just a few more minutes”.

Tales of Kenzera’s breezy pace is largely due to its low degree of difficulty. Some platforming parts feature insta-kill spikes, and some nastier adversaries appear near the finish of the game, however these hurdles are more like incredibly tiny setbacks than true trials to overcome. If Zau dies, he will nearly always resurrect within a second or two of where he died. During fight, Zau has numerous “outs” for tougher encounters in the form of a meter that he may use to either heal himself or utilize super attacks that quickly remove adversaries off the screen.

Zau can use enhancements to help alleviate any future suffering. A skill tree improves the abilities of his masks, his health and super meter can grow, and he can even equip trinkets that provide additional boosts such as reducing enemy damage or increasing damage dealt. In Metroidios, power creep is unavoidable, but in this case, the vast bulk of what you obtain becomes overwhelming.

Between the ease of navigation, the low base difficulty, and the abundance of options to further tone things down, the purpose is clear: the people behind Tales of Kenzera want as many people as possible to appreciate the game’s narrative, even if it means sacrificing the actual game design. To some extent, accessibility is desirable, and with a publisher like EA, I’m sure it’s inescapable. We live in a time when the game industry prioritizes getting as many people to play as possible, so I see why narrative is important here.

However, there is a darker aspect to this design concept that I find difficult to ignore. Despite playing the game and completing everything it had to offer (with a platinum trophy to show for it), I couldn’t think of any particularly memorable level design or combat encounter. The experience is dull, and it puts me in a trance-like state. I could nearly sleepwalk through each task without having to concentrate too hard or process any individual moments.

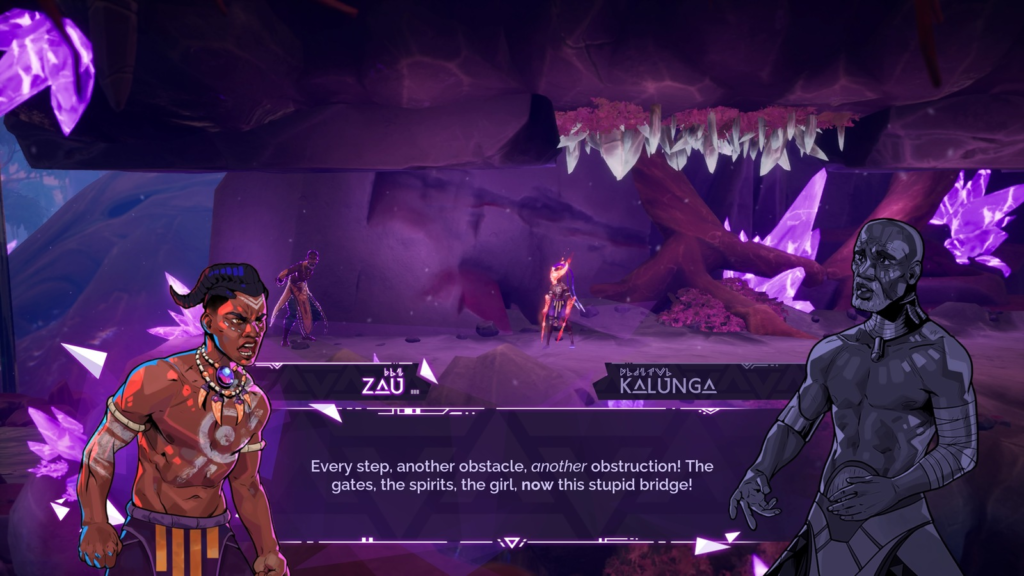

This comfortable style caused a detachment from the emotional weight that Zau felt throughout the novel. Early on, a bridge beneath Zau breaks, forcing him to take an uncomfortable detour. In response, Zau emotionally collapses and rants about how everything was going wrong in a way that seemed completely out of scale to me as a player. For Zau, this was a dramatic tipping point of terrible setbacks. For me, this was just a few more minutes of uneventful platforming. This separation grows as the game delves deeper into his fear, worry, and desperation. In order to be as simple to enjoy as possible, Tales of Kenzera sacrifices its capacity to completely convey the weight of the tale it wishes its players to experience.

That is not to suggest that Tales of Kenzera should be brutally challenging; rather, I do not believe the game should be painless. There must be some form of friction or struggle to keep you involved and in sync with Zau’s plight. This isn’t only a problem with Tales of Kenzera; I encountered a similar issue with Metroid Dread in the past. That game’s title clearly explains its mission: to make you feel dread. However, Dread, like Tales of Kenzera, makes similar compromises in that any death simply sends you back a few seconds to try again. With such a framework in place, how much dread can any obstacle actually evoke?

Tales of Kenzera is now in a predicament. It has a strong story hook, and its overall visual direction, as well as the usage of African culture as a backdrop for its location, lends it a distinct style. Even the foundation of its gameplay mechanics is decent enough that I wouldn’t label it terrible or mediocre. Tales of Kenzera is enjoyable, but it is obviously missing something, and I believe that something is the kind of tension that only video games can bring in giving Zau’s quest weight. I don’t believe that parting with a truly wonderful game can be as painless as parting with someone you love.

Review Overview

Gameplay – 70%

Controls – 72%

Aesthetics – 68%

Content – 65%

Accessibility – 75%

Value – 70%

Overall Rating – 70%

GOOD

Summary: Tales of Kenzera: ZAU is built on a great basis, but it stresses narrative above gameplay design. Rather of allowing its gameplay and narrative to complement one another, it foregoes some of the medium’s distinguishing features in favor of a competent although uninteresting experience that fails to give its subject matter adequate attention.